Complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer

Introduction

Data of the World Health Organization (GLOBOCAN database) showed that colorectal cancers are the second most common cancers in females and the third in males, with 1.8 million new cases and almost 861,000 deaths in 2018 (1). In the United States, annually, approximately 145,600 new cases of large bowel cancer are diagnosed, of which 101,420 are colon (2). In the 1980s, the idea of total mesorectal excision (TME) was presented by Heald et al. (3). Basis of TME was the embryological evolution of the rectum, dissection with embryological planes of dorsal mesentery yields a scatheless specimen which includes all vascular and lymphatic pathways and lymph nodes. This dissection provides more chance for clean circumferential margin (4). TME changed the rectal cancer surgery basics and also affected outcomes. Local recurrence rates decreased from 30–40% to 5–15% by TME revolution (5).

Hohenberger et al. (6) applied TME philosophy for the surgery of colon cancer. Their study showed that visceral and parietal peritoneum were covered the colon, like a sheath and this was similar with mesorectum anatomy by the way they put forward the idea of complete mesocolic excision (CME). Survival rates increased from 82.1% to 89.1% and local recurrence rates decreased from 6.5% to 3.5%.

With the description of CME, it is stated that more standardized resection can be achieved in colon cancer surgery. CME dissection aims to ligate the vessels at their origin [central vascular ligation (CVL)] and to provide a better pathologic specimen quality which includes all lympho-vascular pathways, and nodal components, with respect to the embryological anatomy (7). CME resection specimen should contain an intact surface with all possible tumor spreading routes (8).

Several authors have also reported that survival and local recurrence rates are better with CME (9-13). However, almost all of these studies are retrospective cohort series and many of these have no comparison group (14-17). The most important thing is; any randomized controlled trial for CME has not been published yet.

Embryology and anatomy of the mesocolon

It is necessary to understand the anatomical properties of mesocolon for describing CME. The adult residue of distal mid-gut’s and proximal hindgut’s primitive dorsal mesenteric tissue generates the mesocolon (18). At the end of the 4th embryologic week, mid-gut’s rotation [counterclockwise 270° and along the axis of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA)] determines the dorsal mesentery and the mesocolon (19-21).

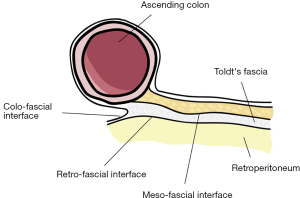

Carl Toldt (22) showed that there is an extra fascial plane between the mesocolon and retroperitoneum and called it as “Toldt’s Fascia”. Culligan et al. (23) describe the mesocolic anatomy in detail. They defined three points: (I) Mesocolon starts at ileocecal level and continues up to rectosigmoid level; (II) Mesocolon of the transvers colon and the mobile part of sigmoid mesocolon does not include “Toldt’s Fascia”. Rest of the mesocolon (ascending, descending, non-mobile part sigmoid colon’s) are apposed to the retroperitoneum and “Toldt’s Fascia” is defined in these places; (III) confluence of sigmoid mesocolon and mesorectum is the inception of proximal rectum. Three surgical interfaces between two contiguous structures were described by Heald (3): (I) “Colo-fascial interface” (confluence of colonic surface and “Toldt’s Fascia”); (II) “Meso-fascial interface” (confluence of mesocolon and “Toldt’s Fascia”); (III) “Retro-fascial interface” (confluence of retroperitoneum and “Toldt’s Fascia”) (24) (Figure 1).

Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the lymphatic channels within the mesocolon are densely present in both submesothelial connective tissue and interlobular septations (7,25). In the light of these results, any degradation in the mesocolic surface disrupts lympho-vascular and neuro-perineural networks and may cause tumoral tissue to be spilled into the surgical dissection field (7).

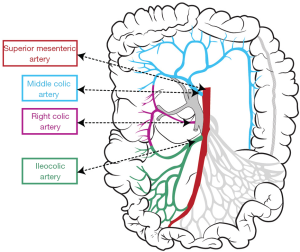

Vascular anatomy of the right colon

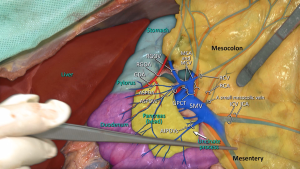

Vascular anatomy should previously be learned in details to perform CME for right colon cancers within the proper anatomical planes. SMA has 2 or 3 major branches that provide the arterial blood supply of right colon (Figure 2). The most important one of these branches is “ileocolic artery” (ICA). Presence of “right colic artery” (RCA)—which originates from SMA—differs from 0% to 63% at cadaveric reports (26); it can be originated from ICA or “middle colic artery” (MCA) (27). MCA divides into right and left branches but it has many anatomical variations; can be absent (up to 25%), doubled or accessory MCA (28).

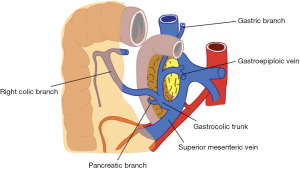

Two main arteries—ICA and RCA—are ligated during CME so topography of these two arteries towards SMA should be known. Both these arteries have important neighborliness with “superior mesenteric vein” (SMV). In 63–100% of the cases RCA runs anterior to the SMV, and ICA crosses anteriorly in 17–83% of cases (26,27,29).

Also venous anatomy of the right colon and variations of the venous anatomy should be known to avoid vascular complications during CME. Venous blood flow of cecum, ascending colon, and the right side of transverse colon drain into SMV. Topographical anatomy of right colic vein (RCV), superior RCV, gastrocolic trunk and middle colic vein (MCV) has too many variations (28,29). The confluence of right gastroepiploic vein, superior RCV and anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein which is known as “gastrocolic trunk of Henle” present in 46–70% cases (27,30) (Figure 3). Study of Yamaguchi et al. (31) showed that MCV has two variations. It can join directly with the SMV (in 84.5% of the cases) or with the gastrocolic trunk (in 12.1% of the cases). Also RCV has two variations, it can join directly with the SMV (in 56% of the cases) or with the gastrocolic trunk (in 44% of the cases).

Preoperative preparation and technique of CME

Preoperative preparation

In this part we will describe our daily practice. In our clinic, mechanical bowel preparation and/or oral antibiotics are not being used before right colon surgery. We give a glycerin enema once or twice before surgery. As antibiotic prophylaxis, we prefer one gram of first-generation cephalosporin and 500 mg of metronidazole as single dose half-an-hour before surgery. In case of necessary situations we prolong antibiotic use for 24–48 hours postoperatively. If there is no contraindication, we start low molecular weight heparin the day before surgery for venous thrombosis prophylaxis.

Surgical technique of open CME

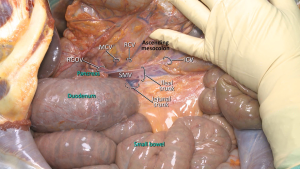

A “lateral-to-medial” approach is usually preferred in open CME technique. The dissection starts with the lateral peritoneal fold, and then continues in the mesofascial plane towards medially (27,32). Mesocolon of the right colon is mobilized towards the root of superior mesenteric vessels. Ascending colon, caecum and mesocolon are separated from retroperitoneum with sharp dissection towards the upper border of the duodenum and pancreatic uncinate process (27,33) (Figure 4). Duodenal Kocherization in the original description of Hohenberger et al. (6) is not routinely performed (33). The autonomic nervous plexus which is situated close to SMA should be preserved during mobilization. When mesocolon and right colon is fully mobilized, vascular ligations begin from ICA. Both structures (ileocolic and right colic vessels) are ligated from their origin at SMA and SMV (Figure 5). The dissection is performed through superior mesenteric vessels and all associated fatty tissue and lymph nodes are harvested (33).

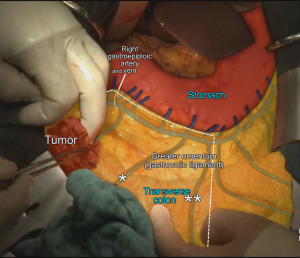

MCA’s right branch is ligated for cecum and ascendant colon cancers, and transvers colon is prepared for transection at the level of middle colic vessels (6). Also surgical approach is slightly different for hepatic flexure and proximal transverse colon cancers. Primarily right gastroepiploic artery—that runs with a vertical plan to transverse colon—is transected to enter the lesser sac. The MCA and MCV both are ligated at closest point of their origin (SMA and Henle’s trunk respectively) (6,33,34). If there are suspected lymph nodes around the head of the pancreas, these lymph nodes are removed by ligating from the root of the right gastroepiploic artery, also—if possible—superior pancreaticoduodenal artery should be preserved during dissection (6,27) (Figure 6). After the transection of distal ileum and transvers colon, the resection is completed and the anastomosis is performed by hand-sewn sutures or linear staplers.

Surgical technique of laparoscopic CME

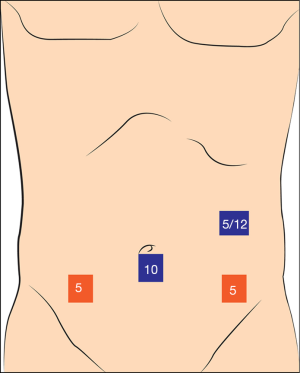

At first, a 10 mm camera port is placed to umbilicus. We start with 5 mm left upper quadrant trocar, we change it to 12 mm if we decide to do intracorporeal anastomosis. 5 mm port is placed to right lower quadrant and another 5 mm port is placed to left lower quadrant (Figure 7). Operation is generally done under 20° left tilted slight “Trendelenburg position”.

Opposite to open CME, ‘medial-to-lateral’ approach is recommended in laparoscopic technique. In very rare special situations, ‘lateral-to-medial’ approach may also be performed. The dissection begins throughout the superior mesenteric axis close to mesenteric vessels. Right colon vessels (ICA, ICV, RCV and RCA) are ligated at their origin (35). Sharp dissection continues in the fascial plane between the retroperitoneum and mesocolon, to reach the lateral abdominal wall. With the help of this dissection the head of the pancreas is widely separated from transverse colon. For cecum or ascending colon cancers, similar to the open surgery, right branch of middle colic vessels are ligated at their origin and transvers colon is transected at the level of middle colic vessels. For full mobilization of the right colon, hepatic flexure is mobilized, ileocecal peritoneal folds and right lateral peritoneal fold are separated. The ileum is transected at approximately 15–20 cm proximal from the ileocecal valve.

For proximal transverse colon or hepatic flexure cancers, there are some additional manipulations to previous description. The middle colic and right gastroepiploic vessels are ligated at their origin. The variations of venous anatomy should be well known and the dissection should be performed carefully to avoid venous injuries (27,30). Sub-pyloric lymphadenectomy is carried out. The right part of great omentum is resected totally (36). The ileum is transected at approximately 5–10 cm proximal from the ileocecal valve and transverse colon is transected at least 10 cm distal from the tumor.

Anastomotic technique (intracorporeal or extracorporeal) depends on the experience and choice of the surgeon. For intracorporeal anastomosis, a mini-Pfannenstiel incision is generally used for the extraction of the specimen. For extracorporeal anastomosis, a mini vertical incision at the level of the umbilicus is generally used. Several studies showed that ‘cranio-caudal’ or ‘top-to-down’ approaches are also appropriate for CME (37-39). Robotic right CME which is another alternative minimally invasive technique, is safe and feasible according to new studies (40-42).

Quality of surgical specimen

The pathological evaluation is well described and standardized (43-45). The specimens were graded as mesocolic, intramesocolic, and muscularis propria plane. Mesocolic plane, defined as “good” plane, has intact mesocolon. Intramesocolic plane, defined as “moderate” plane, has irregular disruption in the mesocolon, but they do not reach down to the muscularis propria. In muscularis propria plane, defined as “poor” plane, the breaches in the mesocolon reaches down to the muscularis propria.

Many studies showed that CME and CVL produces high quality surgical specimens (12,13,35,44). A systematic review revealed that more harvested lymph nodes, larger mesenteric area, and longer distance from the tumor to vascular tie were achieved by CME technique (46).

Nesgaard and colleagues (47) suggested in their postmortem study starting the dissection at the left of the SMA to achieve radical clearance of the lymphovascular bundles. In the same study, the authors defined the quality of the specimen as the weight of the lymphatic dissection rather than the high tie vascular ligation (47).

Oncologic outcomes of CME in the literature

In the meta-analysis encompassing 8,586 patients, comparing CME and non-CME published by Wang et al. (46) CME had better 3 and 5 years survival rates even though CME was associated with more complications.

Siani et al. (48) reported morbidity rate of 35.5%, mortality rate of 0.5% and average lymph node number of 27±3 in their study of 600 patients. They reported recurrence in 177 (29.5%) patients and overall survival of 83%. In the subgroup analysis overall survival rates were 88.7% in stage 2, 72.4% in stage 3A/B, 71.4% in apical lymph node negative stage 3C and 27.7% in apical lymph node positive stage 3C patients.

Alhassan et al. (49) demonstrated that the complications associated with CME were 22.5%. In their systematic review, only Bertelsen et al. (50) reported intraoperative outcomes and they indicated that intraoperative organ injuries, especially splenic and superior mesenteric vein injuries, were significantly higher in CME compared with non-CME (CME: 9.1% vs. non-CME: 3.6%, P<0.001). But, in the same study the other complications were similar.

Merkel et al. (51) analyzed the transformation from non-CME to CME during 1978–2009 in four different stages. They reported an increase in the overall morbidity (rising from 1.8% to 3.7%); however mortality during the hospital stay is not changed. In addition, locoregional recurrence decreased from 6.7% to 2.1% for all stages, and from 14.8% to 4.1% for stage 3 patients (P=0.046). Distant organ metastasis was reported to decrease from 18.9% to 13.3% (P=0.01). Although not statistically significant, 5-year overall survival gradually increased; nonetheless 5-year cancer related survival increased from 61.7% to 80.9% (P=0.01) (51).

In our unpublished study, CME produced similar pathologic outcomes to conventional colectomy except for its association with a higher number of harvested lymph nodes. In CME patients, 3-year overall survival rate was higher with no statistical significance (CME: 94.4% vs. non-CME: 86.4%, P=0.13).

Two important studies have been published about survival of CME (9,52). Kontovounisios et al. (52) evaluated 5,246 patients in their systematic review, and they indicated the local recurrence rate was 4.5%, and 5-year overall survival was 58.1%. In the other important study showed that disease-free survival rates were higher in the CME group for stage I–III colon cancer (100%, 91.9%, and 73.5%, respectively) (9). Some different studies are summarized in Table 1 (6,9,10,17,44,51,53-56).

Table 1

| Reference | Harvested lymph nodes | 5-year local recurrence | 5-year overall survival | 5-year disease free survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical technique | Number | Plane of surgery | Rate (%) | Plane of surgery | Rate (%) | Plane of surgery | Rate (%) | ||||

| Hohenberger et al. (6) | CVL | 32 | Ms | 4.90 | Ms | 85 | Ms | NR | |||

| West et al. (44) | CVL | 30 | Ms | 4.90 | Ms | 85 | Ms | NR | |||

| Non-CVL | 18 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 70 | Non-Ms | NR | ||||

| Siani et al. (10) | CVL | 30 | Ms | NR | Ms | 82.6 | Ms | 73.8 | |||

| Non-CVL | 18 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 60 | Non-Ms | 59.7 | ||||

| Kanemitsu et al. (17) | CVL | 31 | Ms | 6 | Ms | 84.5 | Ms | 91.6 | |||

| Bertelsen et al. (9) | CVL | 36 | Ms | 11.3 | Ms | 74.9 | Ms | 85.8 | |||

| Non-CVL | 20 | Non-Ms | 16.2 | Non-Ms | 69.8 | Non-Ms | 75.9 | ||||

| Bae et al. (53) | CVL | 28 | Ms | NR | Ms | 90.3 | Ms | 83.3 | |||

| Merkel et al. (51) | CVL | 32 | Ms | 4.1 | Ms | NR | Ms | 80.9 | |||

| Non-CVL | 18 | Non-Ms | 14.8 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 61.7 | ||||

| Kotake et al. (54) | CVL | 18 | Ms | NR | Ms | 91.9 | Ms | NR | |||

| Non-CVL | 11 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 90.6 | Non-Ms | NR | ||||

| Agalianos et al. (55) | CVL | 27 | Ms | NR | Ms | 81.3 | Ms | 84.6 | |||

| Non-CVL | 18 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 70.9 | Non-Ms | 76.4 | ||||

| Gao et al. (56)* | CVL | 24 | Ms | NR | Ms | 97.2 | Ms | 92.2 | |||

| Non-CVL | 20 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 98.3 | Non-Ms | 90 | ||||

| Our unpublished study*,& | CVL | 42 | Ms | NR | Ms | 94.4 | Ms | NR | |||

| Non-CVL | 34 | Non-Ms | NR | Non-Ms | 86.4 | Non-Ms | NR | ||||

All of these series include both right and left colon cancer results. *, 3-year follow-up; &, only right colon cancer. CME, complete mesocolic excision; CVL, central vascular ligation; Ms, mesocolic plane; NR, not reported.

Unfortunately, many studies have significant limitations, being generally retrospective and non-homogeneous, so that at the moment a definitive high level of evidence cannot be drawn and thus no strong grade of recommendation may be assigned (24). The study designs that investigate the CME technique are listed in Table 2 (9,12,13,35,48,50,51,54,55,57-59).

Table 2

| First author | Year | Country | Design | Journal | Right-sided tumors (CME/total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West et al. (57) | 2010 | UK | Retrospective | Dis Colon Rectum | 58/141 |

| Bertelsen et al. (35) | 2011 | Denmark | Retrospective | Colorectal Dis | 53/118 |

| Galizia et al. (13) | 2014 | Italy | Prospective | Int J Colorectal Dis | 45/103 |

| Storli et al. (12) | 2014 | Norway | Prospective | Tech Coloproctol | 45/102 |

| Bernhoff et al. (58) | 2015 | Sweden | Retrospective | Eur J Surg Oncol | 684/1,309 |

| Bertelsen et al. (9) | 2015 | Denmark | Retrospective | Lancet Oncol | 189/686 |

| Kotake et al. (54) | 2015 | Japan | Retrospective | Int J Colorectal Dis | 463/926 |

| Bertelsen et al. (50) | 2016 | Denmark | Retrospective | Br J Surg | 278/1,168 |

| Merkel et al. (51) | 2016 | Germany | Retrospective | Br J Surg | 506/859 |

| Siani et al. (48) | 2017 | Italy | Retrospective | Am J Surg | 486/600 |

| Olofsson et al. (59) | 2016 | Sweden | Retrospective | Colorectal Dis | 1,694/2,086 |

| Agalianos et al. (55) | 2017 | Greece | Retrospective | Ann Gastroenterol | 71/139 |

CME, complete mesocolic excision.

Prospective randomized trials are needed in large series to allow CME to be considered the gold standard for right colon cancer surgery (24). The results of the prospective randomized ongoing RELARC and COLD studies on CME are eagerly awaited (60,61).

Conclusions

The morbidity of CME is generally higher than the conventional right hemicolectomy. CME needs detailed anatomical knowledge and experience on oncological colon surgery. The CME with CVL offers high quality specimen which possibly reflect good long term oncologic outcomes. Until now, published series on CME are mostly retrospective and non-homogenous. For that reason the interpretation of oncological results should be judged cautiously. The quality of evidence is limited and does not consistently support the superiority of CME.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mehmet Ayhan Kuzu MD, for sharing CME technique images and Suat Erus MD, for his drawings.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Roberto Bergamaschi and Mahir Gachabayov) for the series “Right Colon Cancer Surgery: Current State” published in Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ales.2019.07.08). The series “Right Colon Cancer Surgery: Current State” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 2019;144:1941-53. [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery--the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg 1982;69:613-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quirke P, Steele R, Monson J, et al. Effect of the plane of surgery achieved on local recurrence in patients with operable rectal cancer: a prospective study using data from the MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG CO16 randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2009;373:821-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, et al. Rectal cancer: the Basingstoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978-1997. Arch Surg 1998;133:894-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, et al. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:354-364; discussion 355-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siani LM, Garulli G. The importance of the mesofascial interface in complete mesocolic excision. Surgeon 2017;15:240-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Søndenaa K, Quirke P, Hohenberger W, et al. The rationale behind complete mesocolic excision (CME) and a central vascular ligation for colon cancer in open and laparoscopic surgery: proceedings of a consensus conference. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:419-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, et al. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:161-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siani LM, Pulica C. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation in right colon cancer: Long-term oncologic outcome between mesocolic and non-mesocolic planes of surgery. Scand J Surg 2015;104:219-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotake K, Mizuguchi T, Moritani K, et al. Impact of D3 lymph node dissection on survival for patients with T3 and T4 colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:847-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Storli KE, Sondenaa K, Furnes B, et al. Short term results of complete (D3) vs. standard (D2) mesenteric excision in colon cancer shows improved outcome of complete mesenteric excision in patients with TNM stages I-II. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18:557-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F, et al. Is complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation safe and effective in the surgical treatment of right-sided colon cancers? A prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:89-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang JT, Lai HS, Huang J, et al. Long-term oncologic results of laparoscopic D3 lymphadenectomy with complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer with clinically positive lymph nodes. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2394-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho MS, Baek SJ, Hur H, et al. Modified complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation for the treatment of right-sided colon cancer: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors. Ann Surg 2015;261:708-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin JW, Amar AH, Kim SH, et al. Complete mesocolic excision with D3 lymph node dissection in laparoscopic colectomy for stages II and III colon cancer: long-term oncologic outcomes in 168 patients. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18:795-803. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, Kimura K, et al. D3 Lymph Node Dissection in Right Hemicolectomy with a No-touch Isolation Technique in Patients With Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:815-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banister LH. Anatomy of the large intestine In: Anatomy Gray’s. editor. The Anatomical Basis for Medicine Surgery. 38th ed. Churchil Livingstone, 1995:1774-87.

- Brookes M, Zietman A. Alimentary tract. In: Clinical embryology, a color atlas and text. CRC Press, 2000:148-152.

- Jorge JMN, Habr-Gama A. Anatomy and embryology of the colon, rectum, and anus. In: Steele SR, Hull TL, Read TE, et al. editors. The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. 3rd ed. Springer, 2007:1-22.

- Sadler TW. The digestive system. In: Langman's medical embryology. 9th ed. Lippincott Wilkins and Williams, 2003:283-321.

- Toldt C. Splanchology - general considerations. In: Toldt C, Della Rossa A, editors. An Atlas of Human Anatomy for Students and Physicians. New York: Rebman Company, 1919:408.

- Culligan K, Coffey JC, Kiran RP, et al. The mesocolon: a prospective observational study. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:421-8; discussion 428-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siani LM, Garulli G. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation in right colon cancer: A comprehensive review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016;8:106-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Culligan K, Sehgal R, Mulligan D, et al. A detailed appraisal of mesocolic lymphangiology--an immunohistochemical and stereological analysis. J Anat 2014;225:463-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ignjatovic D, Sund S, Stimec B, et al. Vascular relationships in right colectomy for cancer: clinical implications. Tech Coloproctol 2007;11:247-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Açar Hİ, Comert A, Avsar A, et al. Dynamic article: surgical anatomical planes for complete mesocolic excision and applied vascular anatomy of the right colon. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57:1169-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakorafas GH, Zouros E, Peros G. Applied vascular anatomy of the colon and rectum: clinical implications for the surgical oncologist. Surg Oncol 2006;15:243-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim NK, Kim YW, Han YD, et al. Complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for colon cancer: Principle, anatomy, surgical technique, and outcomes. Surg Oncol 2016;25:252-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lange JF, Koppert S, van Eyck CH, et al. The gastrocolic trunk of Henle in pancreatic surgery: an anatomo-clinical study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2000;7:401-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi S, Kuroyanagi H, Milsom JW, et al. Venous anatomy of the right colon: precise structure of the major veins and gastrocolic trunk in 58 cadavers. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:1337-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Culligan K, Walsh S, Dunne C, et al. The mesocolon: a histological and electron microscopic characterization of the mesenteric attachment of the colon prior to and after surgical mobilization. Ann Surg 2014;260:1048-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Killeen S, Kessler H. Complete mesocolic excision and central vessel ligation for right colon cancers. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18:1129-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gouvas N, Pechlivanides G, Zervakis N, et al. Complete mesocolic excision in colon cancer surgery: a comparison between open and laparoscopic approach. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1357-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen CA, Bols B, Ingeholm P, et al. Can the quality of colonic surgery be improved by standardization of surgical technique with complete mesocolic excision? Colorectal Dis 2011;13:1123-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mori S, Baba K, Yanagi M, et al. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with radical lymph node dissection along the surgical trunk for right colon cancer. Surg Endosc 2015;29:34-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamzaoglu I, Ozben V, Sapci I, et al. "Top down no-touch" technique in robotic complete mesocolic excision for extended right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis. Tech Coloproctol 2018;22:607-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuda T, Iwasaki T, Mitsutsuji M, et al. Cranial-to-caudal approach for radical lymph node dissection along the surgical trunk in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. Surg Endosc 2015;29:1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuda T, Iwasaki T, Sumi Y, et al. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer using a cranial approach: anatomical and embryological consideration. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:139-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozben V, Aytac E, Atasoy D, et al. Totally robotic complete mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer. J Robot Surg 2019;13:107-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bae SU, Yang SY, Min BS. Totally robotic modified complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for right-sided colon cancer: technical feasibility and mid-term oncologic outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:471-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spinoglio G, Bianchi PP, Marano A, et al. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Right Colectomy with Complete Mesocolic Excision for the Treatment of Colon Cancer: Perioperative Outcomes and 5-Year Survival in a Consecutive Series of 202 Patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:3580-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- West NP, Morris EJ, Rotimi O, et al. Pathology grading of colon cancer surgical resection and its association with survival: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:857-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, et al. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:272-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:1718-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Gao Z, Shen K, et al. Safety, quality and effect of complete mesocolic excision vs non-complete mesocolic excision in patients with colon cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:962-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nesgaard JM, Stimec BV, Soulie P, et al. Defining minimal clearances for adequate lymphatic resection relevant to right colectomy for cancer: a post-mortem study. Surg Endosc 2018;32:3806-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siani LM, Lucchi A, Berti P, et al. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation in 600 right total mesocolectomies: Safety, prognostic factors and oncologic outcome. Am J Surg 2017;214:222-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alhassan N, Yang M, Wong-Chong N, et al. Comparison between conventional colectomy and complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis: A review of CME versus conventional colectomies. Surg Endosc 2019;33:8-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, et al. Short-term outcomes after complete mesocolic excision compared with 'conventional' colonic cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2016;103:581-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Merkel S, Weber K, Matzel KE, et al. Prognosis of patients with colonic carcinoma before, during and after implementation of complete mesocolic excision. Br J Surg 2016;103:1220-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kontovounisios C, Kinross J, Tan E, et al. Complete mesocolic excision in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2015;17:7-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bae SU, Saklani AP, Lim DR, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation for right-sided colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2288-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotake K, Kobayashi H, Asano M, et al. Influence of extent of lymph node dissection on survival for patients with pT2 colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:813-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agalianos C, Gouvas N, Dervenis C, et al. Is complete mesocolic excision oncologically superior to conventional surgery for colon cancer? A retrospective comparative study. Ann Gastroenterol 2017;30:688-96. [PubMed]

- Gao Z, Wang C, Cui Y, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Complete Mesocolic Excision in Patients With Colon Cancer: Three-year Results From a Prospective, Nonrandomized, Double-blind, Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- West NP, Sutton KM, Ingeholm P, et al. Improving the quality of colon cancer surgery through a surgical education program. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:1594-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernhoff R, Martling A, Sjovall A, et al. Improved survival after an educational project on colon cancer management in the county of Stockholm--a population based cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015;41:1479-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olofsson F, Buchwald P, Elmstahl S, et al. No benefit of extended mesenteric resection with central vascular ligation in right-sided colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:773-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu JY, Xu L, Xue HD, et al. The Radical Extent of lymphadenectomy - D2 dissection versus complete mesocolic excision of LAparoscopic Right Colectomy for right-sided colon cancer (RELARC) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:582. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Study of Oncological Outcomes of D3 Lymph Node Dissection in Colon Cancer (COLD). (NLM Identifier: NCT03009227). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03009227 (accessed December 4, 2017).

Cite this article as: Zenger S, Balik E, Bugra D. Complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2019;4:70.